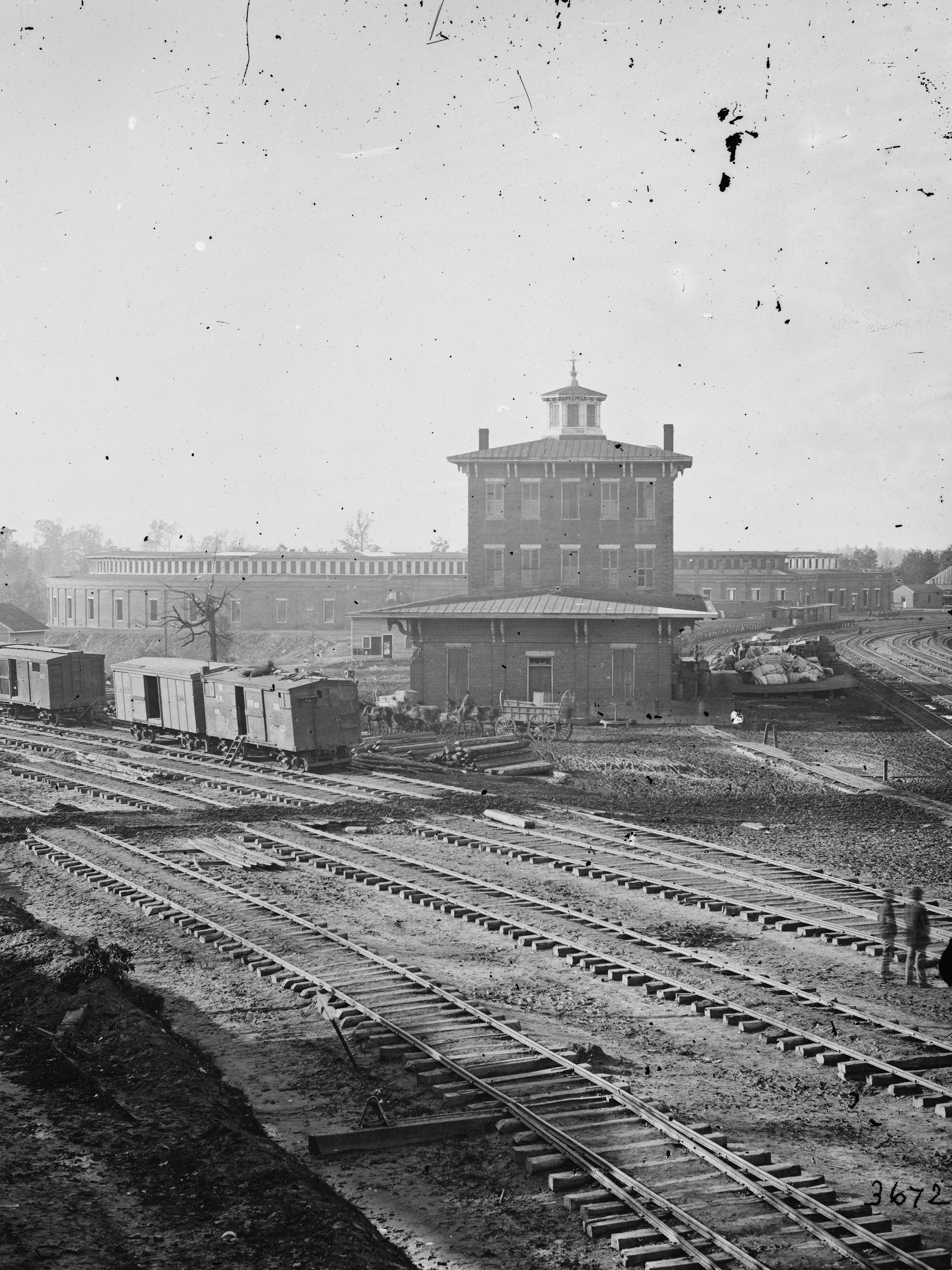

Rail logistics gave Atlanta increasing significance as the war progressed. The main terminal, in photo at left, was as economically and symbolically important to antebellum Atlanta as Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport is to our present-day city.

The names of the trains have changed and more railroads have built into the city in the 150 years since, but Atlanta’s core rail network follows the same roadbeds that were in place during the Civil War. The Gulch in the heart of downtown remains a focal point of rail traffic through the city.

Sherman and Union officers, near today’s Atlanta University Center.

For 36 consecutive days, Union armies besieging Atlanta rained cannon shells into the city. Stephen Davis, author of the book “What the Yankees Did to Us: Sherman’s Bombardment and Wrecking of Atlanta,” researched Union artillery records, Southern newspapers and other sources to determine how many shells were fired.